Worldmaking

The next story in Jones' collection is Nanaboozho and the Great Fisher, but the footnote for the story tells us that the fisher Nanaboozho encounters is actually the constellation and not simply an animal a little bigger than a marten. So that means we need to understand how the fisher became a constellation, which means knowing how the spirit world was created in the first place. We're going to go back to the flood story because the creation of the spirit world takes place in the immediate aftermath.

As always, these are my own reflections on how the traditional stories of the Anishinaabe can be read into our lives today. And welcome to new members, especially my new bestie Karen! Paid subscriptions help keep the lights on and the books coming in, but simply sharing my work on social media or wherever it is you share things really helps.

The flood that was unleashed after Nanaboozho killed the water panther resulted in the deaths of a lot of beings, and although the world was remade that didn't help the beings who had died. Worlds ending and beginning do have a significant cost, and that cost is generally born by those who had nothing to do with the violence. Nanaboozho noticed their spirits roaming aimlessly in the sky with nowhere to rest and decided on a course of action. Wiin (gender neutral pronoun in Anishinaabemowin) asked Turtle to go get some stones, but Turtle was mad because Nanaboozho hadn't included him when he remade the world and he refused to help so Nanaboozho grabbed him and threw him into the lake.

Wow if Turtle was mad before he was furious now so he swam to the bottom and pouted in the middle of the lake. If that sounds familiar, it should. Eventually he came back up for air and Nanaboozho shot an arrow at him, hitting his shell and startling Turtle. All the mud that had gathered on him while he pouted got flung up into the sky.

That mud contained Nokomis' medicines which also got flung across the sky and created Jibiiy Miikan, what you might know as the Milky Way and what we know as the sacred path to the afterlife. Nanaboozho followed that path east to west and at the end wiin created the spirit world. Wiin was there for a long time, creating everything that needed to be created. Rocks and trees, animals. Everything as it should be.

Nanaboozho's brother Jiibayaboos became the keeper of that path. You'll recall that Nanaboozho killed two of wiin's brothers, but they're manitous like wiin so they don't stay dead and Jiibayabos wanted to look after that place, so that's where he went after Nanaboozho killed him.

According to this story, when we pass away we eventually go out the Western Door and along this path. It is sacred, but it is also dangerous with various tests along the way. There is an old man who shows you the path, an old woman who asks you to choose which way to go. There is a strawberry, which is how you know you chose correctly, but don't eat it. There are dogs and a dark gully. You will need to lay tobacco at the right times and make fire but once you are through that gully you'll be where the blue skies are. There is a river with a serpent in it, and many people falter at this point because giant water serpents are scary anywhere you encounter them, but if you lay tobacco he will become a log and you can cross safely to where your family and ancestors are waiting for you.

The Anishinaabe buried people sitting up, with their feet facing West because that's the way they would travel, and if you didn't want an adversary to meet up with you in the afterlife? Face their feet the wrong way, or scatter their bones. So you can see why Indigenous people are so upset about children buried at residential schools or missing women and girls or ancestors hidden in Museum basements. And what of the old man and the old woman? Do they speak English or Anishinaabemowin? What if you get there and because they're Anishinaabe spirits they speak Anishinaabemowin and you can't talk to them because your language was taken from you? How will you know what to do?

When my father passed he wanted to be buried at home with his brother and father, which meant being cremated until we could take him home. We obviously weren't able to put his feet westward, but the urn did have a front and a back, so I placed it with the front facing westward, gave him some tobacco for the journey along with some blueberries and a double double. I hope that was ok. It still makes me smile to remember us all standing there and suddenly needing to figure out which way was west.

In this story Nanaboozho acts out of compassion. Wiin sees the spirits who perished, because of the flood that was unleashed, and wanted to create somewhere for them to rest. But we don't create alone do we, wiin didn't just grab a handful of rocks and throw them into the sky. Wiin reached out to Turtle despite possibly knowing that Turtle was mad and might refuse. We need to remember this in our organizing, to include people we may not get along with. Turtle could have agreed to get the stones and brought back the medicines too, but that's not what happened and Nanaboozho rolled with it. Throwing Turtle into the water wasn't done out of anger, it was an act of trust. We need to remember this too. Keep our plans and strategies adaptable. Sometimes, people who are resistant but also skilled, and maybe mad at us for good reasons, just need to be thrown into it because we trust them to do what we know they are capable of.

Nanaboozho's grandmother had told wiin that "had I not carried out the purpose of my mind, I would never have reared you." The footnote tells us that the purpose of her mind was to make Nanaboozho "an instrument whereby a new order of things should come to pass in the world." Her purpose in raising Nanaboozho was that wiin would bring a new order of things into the world, that wiin would transform the things that needed to be transformed. That's a significant context for how we read Nanaboozho's actions.

Jones also reminds us, in a footnote, that Nokomis is THAT Nokomis. The one who fell from the sky and scattered her medicines on the bottom of the lake. She is mother earth, the first woman without whom none of this would exist. Her daughter Wenona died giving birth to Nanaboozho and wiin's brothers.

In the creation stories the Anishinaabeg tell in the eastern part of the lands we live on, Nokomis is named Gizhiigokwe: Sky Woman. Sky Woman is also known to the Haudenosaunee who have their own stories about her. We've thought about the story of Nokomis falling from the sky and pouting under water until a bear convinced her to come up. I want to add a story from the Michi Saagig Nishnawbe that Leanne Betasamosake Simpson shares in Theory of Water, which I'll be coming back to again as we move through these three connected stories over the next few weeks.

We have many creation stories, something that I'm still getting used to after growing up evangelical but I am coming to value and appreciate this multiplicity, because we do have multiple beginnings. Creation stories are, as Leanne calls them, leaky containers that carry water which seeps out, freezes, evaporates, or nurtures a seed that grows into something else. So I've stopped trying to figure out how they fit together into a single consistent narrative and come to accept that insisting on a single consistent narrative may not be useful.

Diversion: in his book The Bible Says So: What We Get Right (and Wrong) About Scripture's Most Controversial Issues, biblical scholar Dan McLellan points out (in the chapter "The Bible Says God Created the Universe Out of Nothing") that the very beginning of Genesis is mistranslated. Instead of saying "In the beginning ..." it should say "In a beginning ..." That's a profound difference. The first word of the Bible is not, as Dan points out, a definite article. That matters because the Hebrew suggests that there were other beginnings, things that happened before we got to a planet covered in water. McLellan also points out that the second creation account in Genesis 2 is somewhat different, and might actually have been written first with what we read first (Genesis 1) being a correction. The first account (G1) says everything is good. The second account (G2, possibly written first, yes this is confusing kind of like the first Star Wars movie is actually episode 3) finds the earth creature's solitude to be not good. And by the way, in the Hebrew the earth creature doesn't become male until after the separation into two beings: male and female. Translators make choices. Choices have consequences.

I don't want to go into the weeds on this, but I do want to highlight that the evangelical reading I grew up with wasn't inevitable. The text itself offers multiple beginnings, but choices made by the translators make that hard to see. What I find kind of interesting is that the beginning that Simpson is talking about also describes a world covered in water. I'm not going to do a compare and contrast, just pointing out that you don't have to convert to Anishinaabe cosmology to see this kind of possibility in your own stories, whatever those stories might be.

Back to Simpson and her elder Doug Williams-ba.

Early on, when Gizhe Manidoo made the world, everything was beautiful, everyone was kind. But it didn't last, she writes that Williams told her it could be that life is actually not that easy to keep. As a result most things died off. The sun and moon, the land and waters they were all ok but everything that moved and grew was gone. Gizhe Manidoo was bothered, again Williams' word and a charming way to phrase it. I think about myself when I'm bothered, the heavy sigh and retreating to my comfort show which is usually XFiles, maybe Thor: Ragnarok. There were spirits living in the sky who offered to help and they asked Gizhiigokwe (Sky Woman) if she would go down to earth to see what could be done.

She went, and what a mess. She tried, but then her children died so she went back to visit with Gizhe Manidoo and they commiserated for a time. Meanwhile, back on earth, nibi (water) went to work. They moved across the land, reshaping and remaking. Simpson points out they didn't have to. There was little benefit to them right? They were fine on their own. But maybe they weren't. Maybe they needed others, so they looked beyond themselves to the rest of the world. I have a granite stone that came home with me from a campground along Lake Superior. It is round and smooth and I hold it in my hand every day thinking about the amount of time involved to shape the stone that way. Nibi was at this world shaping for a while.

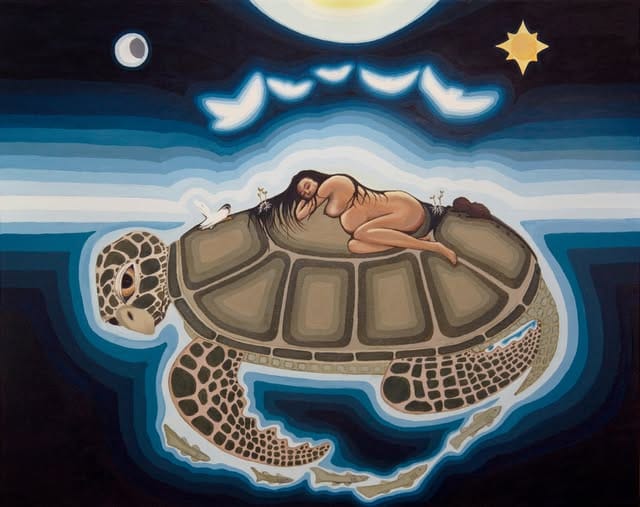

This time when Gizhiigokwe goes down to try again she comes across the flood. Was this worse than before? Have you ever had a flooded basement? Where do you begin? You begin with what's in front of you and what was in front of Gizhiigokwe was animals who had survived the flood because of their own relationship with water, nibi. Chi-Mikinak, a snapping turtle, offered her a place to rest.

Simpson points out that they may not even have been thinking about worldmaking at that point. Just resting together. Taking care of each other. She asks, have you ever noticed a turtle's back? 13 plates in the middle. 28 plates around the outside. Gizhiigokwe recognized that pattern, it was the same pattern her body followed with each moon. For Williams, this is what was missing in Gizhe Manidoo's earlier creations: cycles and renewal. From her place of rest on Chi'Mikinak's back a plan formed. Gizhiigokwe asked for some mud and one by one animals tried and failed until muskrat surfaced with that handful of mud from which everything was built. A world full of cycles and renewal that could remake itself when it had to. Later, when Nanaboozho unleashed the flood, wiin would remember this story and knew what to do.

Gizhiigokwe returned to skyworld where she became the moon, embodying (I love Simpson's repeated use of this word) the cycle of her own body mapped out on the back of Chi-Mikinak. She became the moon, continuing to work with nibi in shaping and remaking the world through tides pulling nibi this way and that, pulling on us too, the water in our bodies.

This is Nanaboozho's grandmother. This is Nokomis who fell from the sky and participated in worldmaking. Who maybe brawled with her sisters and brought medicines from skyworld onto the earth. Whose daughter, Wenona, died in childbirth and who cared for a clot of blood that became a rabbit named Nanaboozho whose purpose was to continue her work of making and remaking. The stories may not fit together neatly, but they do fit together when we think about what they teach us about worldmaking because in this story about Nanaboozho creating the spirit world we see the same forces at work as were present with Nokomis, Gizhiigokwe.

We see compassion. We see making and remaking in concert with others rather than by themselves. We see a respect for rest and commiseration over attempts that did not work. We see the setting aside of time for grief. We see a willingness to step back and let others do the work. Gizhe Manidoo did not get up off their bed to go try again. They trusted Gizhiigokwe even after her first attempt failed. When she came back they didn't grumble, I guess if you want it done right ... just commiserated again while nibi, who noticed what was going on, stepped in. Got things ready for when somebody came back. Tried something different.

So often we keep trying the same strategies again and again, altering minor things but fundamentally doing the same things and when they don't work we get frustrated. Or we try once, maybe twice, and then give up. And I say we because I include myself. I also get frustrated, give up. Sometimes it's ok to give up on a strategy. To commiserate and regroup. To let somebody else try without giving them directions, just see what they do. To involve new people by giving them the time to try. And sometimes we just throw people into the deep end because we know they'll be able to swim. We trust them even if they don't trust themselves.

Nanaboozho was able to re-create the world after the flood and then create the spirit world for a few reasons. Wiin remembered the earlier story, maybe Nokomis had talked about her wild times as a young woman and the things she got up to. Movement elders are so important to listen to and learn from. To read their books and listen to recorded speeches. They remind us that we aren't starting from scratch, that the creation of a more just world has been underway for as long as those who build injustice have existed. If you listen to movement elders you'll find out that they also had elders that they listened to and you can follow those threads of resistance back a long way learning strategies for resistance and rebuilding. One of the criticisms of the Occupy Movement was that they acted new and didn't build alongside Indigenous organizers who had been at it for a while. Nokomis was a movement elder. So is nibi.

Nanaboozho did not act alone. In all of the stories, things tend to go sideways when wiin acts alone. When wiin took their eyes off the geese wiin was flying with, for example. But in this Nanaboozho did not act alone. Wiin invited animals to get a handful of mud. Wiin reached out to Turtle, who was mad about being excluded, to join in the work. Nanaboozho trusted those wiin worked with. Did not micromanage them, did not give them detailed instructions. Wiin came up with a plan, shared what wiin needed in order to make it happen, and trusted them.

And Nanaboozho paid attention to those who had been marginalized by wiin's own actions. The flood had caused harm. It wasn't what wiin intended. The stories about vengeance don't suggest that wiin knew the waters that would be unleashed. We don't always know what the unintended consequences of our actions will be, but we're still responsible. One thing about the western societies we live in is that that they are ok with sacrificing those they make marginal. That is the essence of conservatism: preserving tradition and a particular way of life even at the cost of others. It gets justified all kinds of ways. They should get an education if they want a better job. They should have done this or shouldn't have done that. Neoliberalism has created an economy and a social system that blames those it marginalizes. Nanaboozho does not do this. Wiin was not ok with sacrificing them for some greater good. Wiin notices the spirits wandering the sky with nowhere to go and sets about making a place for them.

Do we make a place in our movements? Do we make a place for the people made marginal by the society we live in?

One last story and then I'll close. I was on a panel recently with Sarah Augustine and Sheri Hoestetler about their book So We & Our Children May Live: Following Jesus in Confronting the Climate Crisis along with Mark Charles, a Navajo activist and writer. Towards the end he remarked that Indigenous peoples need to step more confidently into our role as hosts, the original peoples of these lands. This idea of us as hosts is a good principle for any trans-community solidarity work and is also the basis of Bad Indians Book Club. Trans-community solidarities are so important to everything that is happening right now and we cannot afford to organize as if the issues facing each of our communities are somehow distinct from those facing others.

That's what I'm on about in Bad Indians Book Club, because reading is a place to start. As an Indigenous writer, I acted as a kind of literary host to a range of marginalized authors. First I hosted a series of panel conversations with authors and readers and then I expanded those conversations into this book. It is not, of course, enough to simply read things and develop a better understanding of science, history, memoir, etc. You have to get out there and actually get to know people, show up for them. But books can help demystify, they challenge that single story we often have about each other.

My main beef with leftist organizing is its failure to reckon with stolen land. Its desire to create what is basically a more inclusive settler colonialism. But we're part of that too. Does our organizing invite them in? Do we show up for them just as we expect them to show up for us? There are some stunning examples of that kind of trans-community organizing so I'm not saying that it isn't happening. It really is, we just need more of it. It should be the norm. Indigenous people should be an integral part of social justice movements taking place on our land. We are the hosts.

I liked Mark's phrasing. We need to step more confidently into our role. Not tentatively, not holding back. Confidently, as the original peoples of this place. Aware that we, along with our elder sibling Nanaboozho who for better or worse never lacked confidence, are raised by our (grand)mother the earth with the intention that we will transform it. Raised to be be an instrument whereby a new order of things should come to pass in the world.

And not bossy or full of ego either, Nanaboozho does that too and it always goes sideways when he is like this. But rather, we move confidently. Learning from movement elders. Engaging with and trusting others even if we don't get along or they are mad at us. Making space for those made marginal. Because our struggles truly are connected. None of us are free until all of us are free.

God is Red: A Native View of Religion by Vine Deloria Jr is one of the first books I read by this movement elder. It was published in 1973 and remains a critical book along with his other works. We are, he says, part of nature, not a transcendenent species with no responsibilities to the natural world. Read it thoughtfully, without defensiveness about what you think he misunderstands because he understands more clearly than you might think.

Breaking Free Of Neoliberalism: Canada's Challenge by Alex Himelfarb. If you are as baffled about what neoliberalism is as I am, this is a great little book. It is focused primarily on Canada but it includes a lot of US content because that's where Canadians got it from. Thanks US!

Safety through Solidarity: A Radical Guide to Fighting Antisemitism by Shane Burley and Ben Lorber. I've recommended this before and I'm recommending it again. Great book for how we can work together to root out the antisemitism taught to us by the society we live in and work together towards an unjust world. You can listen to Shane here on Movement Memos, talking about how to fight fascism in a captured state.

The Next Apocalypse: The Art and Science of Survival by Chris Begley continues this theme of surviving together. We really don't seem to understand how disaster works. It's not like the movies, mostly civilizations unravel slowly and build to a crescendo. But in the end, Begley says, it is communities who survive. Not lone survivors. You can also listen to him on, you guessed it, Movement Memos.

And a whole bunch of resources from the people at Indigenous Solidarity with Palestine.

If you're as excited about Bad Indians Book Club being released as I am and would like to be part of the release crew you can sign up here.

And don't forget to join up with the Nii'kinaaganaa Foundation. Every month we collect funds from people living on Indigenous land and redistribute them to Indigenous people and organzers. You can find out more information on the website which is now powered by ghost, which means that you can become a subscriber there just like you are here!