The shores of the sea

Before we get to today's story, I want to return briefly to last week and the story about the Anishinaabeg being careless. Breaking branches, stepping on flowers, making their own path.

There is a swamp behind my house. We call it a swamp, but it's mostly dry and walkable. Just in the spring or if it's been particularly rainy it gets swampy because there's so much clay and nowhere for the water to go. But the other day it was fine. I hadn't been there for a while and I needed some birchbark so I decided to go and see if I could find any. I did not. But I did find an interesting lesson instead, along with a lot of ticks. Yuck.

There's a dense thicket between my yard and the swamp so I have to look for a deer run in order to get through the dense shrubbery and while I did find one, somehow I managed to lose it and I had to make my own path, which meant I broke branches and stepped on flowers and generally made quite the racket before coming out into the open expanse of the swamp. If I was hunting, well you can imagine the lack of success that waited for me. I would have been just standing there in the forest wondering where all the animals went. Before long I found some landmarks (rusty garbage cans that have been out there forever) and realized that I had come in the wrong way, missing my usual path. On the way out, I used another deer run that didn't disappear on me and guess what. No broken branches, did not have to step on any flowers, much quieter.

I haven't even mentioned the thorns that poked at me and grabbed onto my clothes on the way in that were not a problem on the way out. So I had to laugh at myself because in addition to everything else, our stories contain information that is simply practical. Don't push through the brush if you don't have to, making your own paths like some chaos demon. Follow the deer.

Before we go further, hello to new members! Paid subscribers help keep the lights on, but you can expand my audience by sharing this post through email or on social media.

This week we're back with William Jones and the story Nanabushu and the Great Fisher. This story is mentioned on the Environmental Education for Kids website. These are just personal reflections, they are not meant to be seen as an authoritative statement on what these stories mean, as if there was a singular meaning. Which there isn't. I reflect on these stories to put them into conversation with your own, not to try and convert you to the religion of the Anishinaabe.

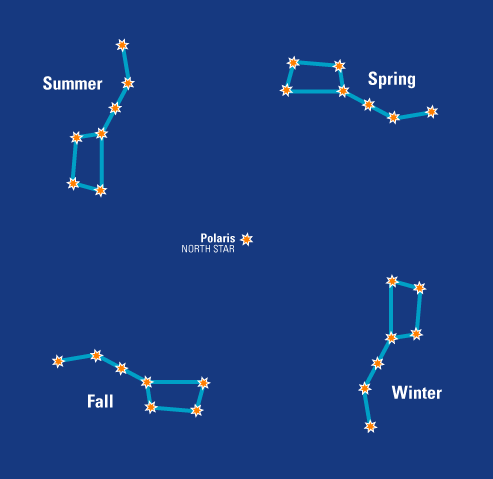

To recap: In re-creating the world after the flood Nanaboozho enlists the help of a reluctant snapping turtle to create the spirit world for all the spirits who had perished during the flood and were stuck in the sky with nowhere to go. In another story, the fisher and his friends form the fellowship of the birds to get spring back but he dies in the process and becomes the constellation you might know as the big dipper but what the Anishinaabe know as the Fisher Star.

The two stories may not actually be connected like they were in my head because the skyworld that Fisher and his friends visit in order to free the birds isn't the one that Nanaboozho created for the spirits who had died. The Apache call the world that Fisher and his friends went to the reflecting world, a place of spirit that is connected to our world but not quite the same. It's kind of funny to think about quantum mechanics and multiverse theory catching up with our traditional cosmologies.

As is often the case, Nanaboozho is out walking and wiin hears somebody singing. Wiin follows the song and comes to a sea where a great fisher is leaping back and forth singing "the shores of the sea meet together, the shores of the sea meet together."

Wow, I wish I could do that, Nanaboozho says. I would never stop. Ever. Oh Fisher, can I do this?

The Fisher responds, Listen Nanaboozho. I began doing this a very long time ago, but I am hungry so while I go get something to eat you can take over. Just please sing the song this way "the shores of the sea meet together, the shores of the sea meet together." Do NOT sing it the other way "the shores of the sea draw apart, the shores of the sea draw apart" because if you do you might drown.

For a day and a night Nanaboozho is having a great time leaping and singing but eventually wiin got tired and wondered, what if I did sing it the other way? Wiin started singing "the shores of the sea draw apart, the shores of the sea draw apart" and guess what happened?

Yeah. The shores of the sea did in fact draw apart and splish splash wiin was taking a bath. Except unlike this photo, there was no shoreline to be seen.

"Hey! Great Fisher Haaaaallpppp." And the Great Fisher shook his head, came back, and halped by singing softly and jumping back and forth bringing the shores back together. After this incident Nanaboozho recognized the Great Fisher as a powerful manitou. Wiin realized that there were other manitou in the world, and told the Great Fisher I understand now that you are older than me. This doesn't necessarily mean older like in years. It means that Fisher was a greater manitou than Nanaboozho. Elder brother, elder sister. It's a term of respect and recognition of greater power or wisdom, not necessarily referring to age although these things do often come with increasing years. Not always. There's old people who grew up during the Civil Rights movement and are still working towards racial justice, there's old people who grew up during segregation and are still working towards racial purity and all of those people grew up during the same decades.

Pay attention to the footnotes, is what I was told when my friend Maya recommended these stories to me (for the third time) and in the footnotes Jones explains that the constellation of the Great Dipper is called the Fisher Star by the Ojibwe, and that is the Great Fisher which the story refers to which is what sent me off on other stories about skyworld and how the Great Fisher became a constellation in the first place.

In As We Have Always Done Leanne Simpson writes about the story of how Fisher became a constellation in the first place as a story of negotiation and treaty, a collective action taken by Otter, Fisher, Wolverine, and Lynx. Wolverine who is named "Gwiingwa'aage" which describes him as the one who came from the shooting star. So it would make sense to include him on this mission to the stars.

To digress a little further, Micheal Wassegijig Price tells a story about Wolverine on his blog Revolving Sky about a star spirit who was doing a flyby, lost control, and collided with the Earth leaving a huge crater. The Anishinaabeg observed the crater while it filled with water, and as trees and grasses emerged on its bank. One day a peevish animal they never met before emerged from the lake. They named this animal Gwiingwa'aage reasoning he must have come with the star.

The crater is, according to Price, in northwestern Quebec. There are a couple of impact craters in northern Quebec which geologically speaking are older than the Anishinaabeg (or humanity itself for that matter) by a few hundred million years but it's an interesting story because of the knowledge it suggests. How did those ancient Anishinaabeg KNOW that something from the stars had collided with the earth? I suppose these things happen. The Barringer Crater in Arizona is only about 50,000 years old, within human existence in the Americas. There is a crater in Kansas that's only 1,000 years old. And the Tunguska Event in Siberia happened just two years after Jones documented these stories.

Wherever it was, the crater in this story was likely a small-scale extinction event that flattened everything for miles around. We know this because the Anishinaabeg watched the crater fill with water, they watched grasses and trees to grow. Water and grasses are quick, but trees take a little longer so this observation likely encompassed generations. Also, wolverines tend towards northern mountainous areas, so the Arizona and Kansas craters are unlikely locations for this story, although Anishinaabeg who traveled and heard stories from the people who lived through those events might have reasoned that the craters in northern Quebec happened the same way. And who knows, maybe Anishinaabeg have other sources of information for their stories.

None of this was my point but it is interesting. And don't even start me on the Dogon people and their knowledge of the Sirius star system which is not visible to the naked eye. An astronomer that Kerry and I talked with a few years ago on our podcast was understandably skeptical that aliens really did visit the Dogon, but he said that these stars might have been visible 10,000 or more years ago which is itself amazing, either way the stories stayed relatively intact for millenia. Bonkers.

In Murdoch's story from last week, which I forgot to mention came from Isaac Murdoch's Trail of Nenaboozho, he concludes with the Six Spirits turning Fisher into what is more commonly known as the Big Dipper, a constellation that moves around the north star. In the spring the Fisher is facing down, water flowing out of him and through the hole in the sky that Fisher and his friends made. In the fall, Fisher is on his back and the blood from his wound paints our trees red before the Old Man begins to blow his breath and make it winter again. It's a cycle, life and death, back and forth. Constant, seasonal reminders of what Fisher did for us while we were wreaking havoc, making our own trails through the underbrush. Fisher's movement through the sky regulates the Old Man, lets him know when it's time to start and when it is time to stop. It is this movement through the sky that drives today's story.

It occurred to me, coming back to Jones' story after reading Murdoch's telling of the Great Fisher and its connection with winter, that the shores would appear to meet together as the ice freezes but that doesn't really make sense does it. If we were to speed up the movement of the Great Fisher in the stars it might look like he was jumping back and forth but that's over the course of an entire year, not back and forth during the winter months. And since Jones is clear that the fisher in this story is the Fisher Star, this is going to take some thought.

There are a number of patterns that run through the Anishinaabe worldview, and one of them is the idea of cycles and enacting your role within them to maintain balance. Each time Gizhe Manidoo added something to creation, it would have destablized it a little. The universe getting along ok until planets appeared. Rock and water getting along ok and then suddenly plants and animals appear. Everything calms down, finds the rhythm to settle into and then bam. Humans. It seems to me that many of these stories of Nanaboozho take place in that chaotic time between the arrival of humans and the achievement of some equilibrium, some kind of predictable cycle that allows for planning and building, which is why so many of these stories show us the consequences of Nanaboozho interfering with or disregarding balance and this one is no exception.

Nanaboozho is told what to do, as well as the consequences but wiin's exhuberance and over-estimation of wiin's own abilities is too much. It's not the first time and if the size of these volumes of stories is any indication it won't be the last either. Yes! I can do this! I can do this forever! Let me do this! Anybody who has spent more than 5 minutes with a toddler can recognize the enthusiasm and complete disregard for personal ability. Predictably, after a couple of days Nanaboozho gets tired and when we get tired we do not make good decisions and decisions have consequences.

The sea in this story is Lake Superior, which is huge. I have travelled along the shores and unlike the other Great Lakes, most of the time you cannot see the other side. It is very much like being at the ocean, except for the southeastern portion called Whitefish Bay where the waters leave Lake Superior to flow past Sault Ste Marie and meander through various lakes and rivers on their way to Lake Huron. I imagine the Great Fisher leaping between the outermost points of this bay: Whitefish Point, Michigan and either Batchawana Bay or Horsehoe Bay in Ontario, his leaping maintaining the integrity of this small bay.

The book that the Environmental Education for Kids got the story from is Lake Superior: The American Lakes Series, written by Grace Lee Nute and published in 1944. According to her Wikipedia page, Nute was born in 1895 in New Hampshire, attended Radcliffe College and got a PhD in American history from Harvard. She went on to be an assistant professor at Hamline University in St Paul where she taught Minnesota history and wrote a good many books about the area. Obviously I needed to get this one so that I could get some context for her inclusion of this story.

There isn't much. The story is, as I suspected, tied to the outlet of Lake Superior which makes sense. It's the only place a being could conceivably be imagined leaping back and forth between shorelines to draw them together. She also says that in order to understand the story, you have to know it refers to the Fisher star/Big Dipper but then doesn't explain anything more about why that matters. There's a lot here about Lake Superior itself and the settlement of the lands around it by early colonists, but nothing more about this story which she tells in the final chapter: "Nanabazho and his followers" (lol). In the midst of retelling many of these stories she gets a lot of things wrong (the water panthers are not an evil god for example) because she's interpreting them through her own Euro-Christian lens, but she brings up an interesting observation from a German traveler in the mid-1800s.

J.G. Kohl wrote about the Chippewa (Ojibwe, Saulteaux, we had many names) and he was baffled that Nanaboozho did not feature in our ceremonies despite Nanaboozho clearly being central in our cosmology, responsible for just about everything in our lives from creation to the end of life. He says that you can't walk down a path without something being named after wiin or your guide telling you that this or that place is where Nanaboozho did something. And that is really interesting because coming from a Christian pov that would look weird. That would be like church never mentioning Jesus. I mean, I'm a little baffled that churches aren't mentioning Palestine given that every story they talk about takes place there. So they talk about Jesus, but they disconnect him from the land where he existed. The Ojibwe clearly did not do that, in fact we kind of do the opposite, centring the land itself and all the beings who are part of that land. Nanaboozho's footprints are all over the lands around Lake Superior and along all the places we live, something made increasingly clear as I build my library of Ojibwe stories from Ojibwe and non-Ojibwe sources. The places where wiin existed matter as much as the stories themselves.

That's an interesting observation because it gets at something that is significantly different between many of the societies that emerged here and western thought. Western stories (including religion) are very often about The One. All of humanity is about to collapse and there is The One who must be protected at all costs to ensure our collective survival. Our stories aren't like that, and neither are our ceremonies. They are rooted in networks and kinships. There is no One. There are many, and from a resistance/governance perspective that is really important. That means that we are all necessary because of what we each bring. Like last week's story. Fisher didn't do it alone, he did it with three friends. He's the Fisher Star because he died and the others got to go home. This week's story emphasizes the importance of Fisher's role in the sky, but it also tells us that somebody else could do that too, that it could be a shared burden. There is no One who will save us. We work together with creation itself, we save ourselves.

So having taken this meandering path, leaping back and forth through a couple of stories where have we landed? Are the shores any closer together, or are they getting farther apart? I have no idea. But it did make me think about a lot of very interesting things and it reminded me that contrary to the treatment our stories get from Grace Lee Nute and others, it is worth taking them seriously as the memory and wisdom of a people. Whitefish Bay may not exist because the Fisher star cycles back and forth above it, but the story tells us that the Ojibwe people lived in a world where the spirits were deeply invested in our lives and in which our actions had consequences that reverberated through many worlds.

We lived in that world once. Many still do. And it isn't that far out of reach.

Our Knowledge is Not Primitive by Wendy Makoons Geniusz is a great book about Ojibwe knowledge systems and the ways in which Eurocentrism has distorted and trivialized Traditional Ecological Knowledge, reduced it to a collection of myths and just so stories. It is worth remembering that the enlightenment period did not just extract gold and furs from the worlds it called new. It extracted our knowledge too, and then synthesized it with other knowledge to build the knowledge base we have today. Imagine what they could have accomplished had they taken us seriously and not just extracted what seemed valuable and then "eased themselves" on the rest.

As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is a book I come back to again and again because she does take our stories seriously as wisdom about governance and relationship. We have everything we need right there in our stories, something I am becoming increasingly convinced of as I go through this project. She does this in Theory of Water: Nishnaabe Maps to the Times Ahead as well.

The Manitous: The Supernatural World of the Ojibwe by Basil Johnston. This is a great introduction to Ojibwe cosmology, who the manitous are and what their roles are in our lives. It kind of answers Kohn's question about why is everything about Nanaboozho except our ceremonies. Because everything isn't about Nanaboozho. Wiin is one of many manitous, and by Nanaboozho's own admission wiin isn't the greatest of them. Nanaboozho is important, our elder sibling, but there's a lot more going on ... and Ojibwe don't worship in the same way that Christians understand it anyway.

Orientalism by Edward Said. Heck. I'm a little ashamed to admit that I only read this recently, it's a pretty important book that gets at a lot of the things I write and think about. He writes about the way that Europe sees and definies the Middle and Near East, defining the other which has consequences for policy decisions. Said is writing primarily about Palestine, but the same factors are at work in the Americas in the ways that people like Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Grace Lee Nute, and Dorothy Reid among so many others tell our stories and talk about us.

Yellowface by R.F. Kuang. This is a novel about a white woman stealing an Asian story. In this novel, June Hayward, a white writer and friend of Chinese American author Athena Liu, takes Liu's unpublished manuscript about Chinese Labour Corps in WW1 and makes it her own after Liu's unexpected death. June Hayward becomes Juniper Song, her full and middle names providing a racially ambiguous nom de plume, and the book becomes a hit. Until suspicion creeps in. This novel takes on social media, the publishing industry, and the unfailing entitlement of white women who are the real victims of every story.

In Bad Indians Book Club, Patty Krawec provides critical space for the ne'er-do-wells, disrupters, red sheep, box-busters, tricksters, and all us rowdy relatives defying expectations. Indigenous people have always been proverbial thorns in the sides of colonizers, and this piercing book does an incredible job of letting the air out of today’s imperialist narratives.

~ Taté Walker, award-winning Two Spirit Lakota storyteller and community-builder

The premise of Bad Indians Book Club is not that Ojibwe stories are the best stories, but that we all have stories about how to live in this world and that those stories matter. Fiction and nonfiction, all we are is story.

If you are as excited about Bad Indians Book Club being released as I am and would like to be part of the release crew let me know.

And don't forget to join up with the Nii'kinaaganaa Foundation. Every month we collect funds from people living on Indigenous land and redistribute them to Indigenous people and organzers. You can find out more information on the website which is now powered by ghost, which means that you can become a subscriber there just like you are here! This month is particularly hard, we've got $7300 in requests, and $1500 to meet them with so if you can hit us with a single donation please do!